From famine to feast // Nüetnigenough, La Tana, and the rise of Brussels' beer restaurants

It’s a sticky Friday night in inner city Brussels, and the footpath on Rue de Lombard is jammed. It’s the eve of the BXLBeerfest beer festival and visiting beer tourists have decamped to Nüetnigenough, loitering in front of the restaurant’s sinewy art nouveau entrance. The restaurant doesn’t do reservations, and those hoping to get a spot have gathered into hungry clumps around the door, beer and menu in hand, sweating and waiting.

The tension of unfed tourists dissipates once inside. Diners are in no mood to vacate their hard-won tables, and the waiters that buzz around aren’t of a mind to hurry them along. Under boxy Futurist canvases, American brewers from Kansas City, Missouri, debate beer with a man possessing a Mitteleuropa accent and a fading Méthode Goat tattoo. They are soon replaced by a couple who proceed to cross-reference Nüetnigenough’s extensive beer menu on their Untappd app while they wait for their orders.

This has been the rhythm at Nüetnigenough (the name roughly translates from Brussels dialect as “never, ever enough”) since Olivier Desmet opened it a little over a decade ago. The restaurant has been a base for him to proselytise for beer as a legitimate accompaniment to a good meal. In the Brussels of 2019 this may seem an unnecessary struggle, but for much of the restaurant’s short life it was an exception, not the rule. So much so that, five years after opening Nüetnigenough, Desmet despaired. For all the new bars and breweries opening in Brussels, the city’s restaurants – with a few exceptions – remained tied to the tried and trusted combination of wine and food, or at best unimaginative and industrially-produced beers. Desmet felt his evangelising mission was failing.

“Composing is a really lonely thing,” he says. “You’re alone with your piece of sheet all day. So I had to go to work, to meet people, and talk with them. And I enjoyed it a lot”

Never, ever enough restaurants

It wasn’t, or not completely. Desmet didn’t know it then, but on the other side of the city centre Valeriotto Bannoni, a young Roman chef was about to a beer restaurant of his own, called La Tana. This one would focus not on the classics of the Belgian tradition, but instead bring together Bannoni’s twin passions – the food of his hometown and the beer of his homeland. Over the subsequent five years a trickle of newly beer-curious chefs and restaurateurs like Bannoni became enough of a flood that by the end of Nüetnigenough’s first decade Desmet has shed his despair for something altogether more optimistic. And not before time. “We were super alone,” he says.

Olivier Desmet didn’t come to Brussels with beer in mind. A jobbing composer from French Flanders, when he first came to live in the city in the early 2000s, bartending helped pay the bills. It also gave Desmet a reason to socialise. “Composing is a really lonely thing,” he says. “You’re alone with your piece of sheet all day. So I had to go to work, to meet people, and talk with them. And I enjoyed it a lot.” Most of this work and talk was done at the Au Soleil bar, where he spent four years “pretending that I spoke really well about beer,” Desmet says. It was there that the first notions of what would become Nüetnigenough took hold, and a falling with Au Soleil’s owner in early 2008 was the nudge he needed to explore his idea properly.

“Everyone said it was not going to be possible – you don’t have wine, only beer. That’s not an Italian restaurant!”

A Coup de Coeur

Six weeks and two property viewings later, together with a couple of friends he signed a lease for a pokey two-room space with an irresistible art nouveau window 250 metres from Brussels’ Grand Place. Desmet’s original idea for an eetcafé – a small food menu and an extensive beer list – was soon junked. They simply did not have the cellar space to keep much beer in site. “The sentence you hear the most in Nüetnigenough is ‘Where are we going to put it?’” Desmet says. “I think the first beer list, there was only 30 beers.” Instead, it became clear that the kitchen needed to do more of the heavy lifting, and Desmet chose to focus on well-executed Belgian classics – rabbit, carbonnade, meatballs, and more – cooked with beer.

But the size also had its benefits. A smaller beer offering meant a judicious selection process. “So we tried to focus on beers and breweries not really well known by people. Only coups de coeur,” says Desmet. A more intimate space also allowed him to be closer to his customers, talking them through the beers he served and how they matched with the food they were eating. The cellar has since expanded to include over 150 beers. Desmet has stayed loyal to early collaborators and the menu now features an extensive selection of Alvinne barrel-aged rarities (including one brewed for the restaurant’s 10th birthday), alongside a meaty lambic list.

Well-trained staff continue to guide customers through the now-extensive list. “In Nüetnigenough, it’s maybe 80% that the beer we sell in the choice of the bartender after talking to the customer,” says Desmet. “We push things, suggest things, and see how people react.”

“Go to Bruges!”

For those early diners, Nüetnigenough was still something of a novelty. Desmet was not the first restaurateur to bring excellent food and interesting, original beers together – hometown boys like Dirk Myny at Les Brigittines, and Alain Fayt at Restobieres were well ahead of him. But Nüetnigenough was relatively inexpensive, focused on beers with a low profile but an excellent reputation (where elsewhere the opposite might have been true), and was right in the centre of Brussels’ tourist district.

“It’s bizarre that you don’t have too many. Either you eat well, and the beer list is poor. Or, you have a beautiful beer list and the food is not great. There’s no balance!”

These were still the early days for Brussels’beer revival, and Nüetnigenough launched before both Moeder Lambic’s satellite Fontainas location opened and Brasserie de la Senne had moved into their Molenbeek-based brewery. “American tourists, they went to Cantillon, then in the evenings they came to Nüetnigenough,” Desmet recalls of his early, out-of-town customers. “They turned to me and asked me, ‘What are we going to do tomorrow?’ We just had to say to these people, ‘Go to Bruges! Because there is nothing else to do here in Brussels!’”

Desmet looked on at beer traditions in other countries that were evolving but he felt he saw only stasis in Brussels. “Five years ago I was quite depressed… There were all these new brewing countries. And what was happening in Belgium? Nothing, just nothing,” he says. Even if he couldn’t see it then through a depressive miasma, the city was beginning to change around Desmet. New bars were opening, new breweries were launching, and the city’s restaurants were about to start catching up.

“Finally,” Desmet says, “it seems like everybody woke up at the same time.”

La Tana in Rome, or La Tana in Brussels?

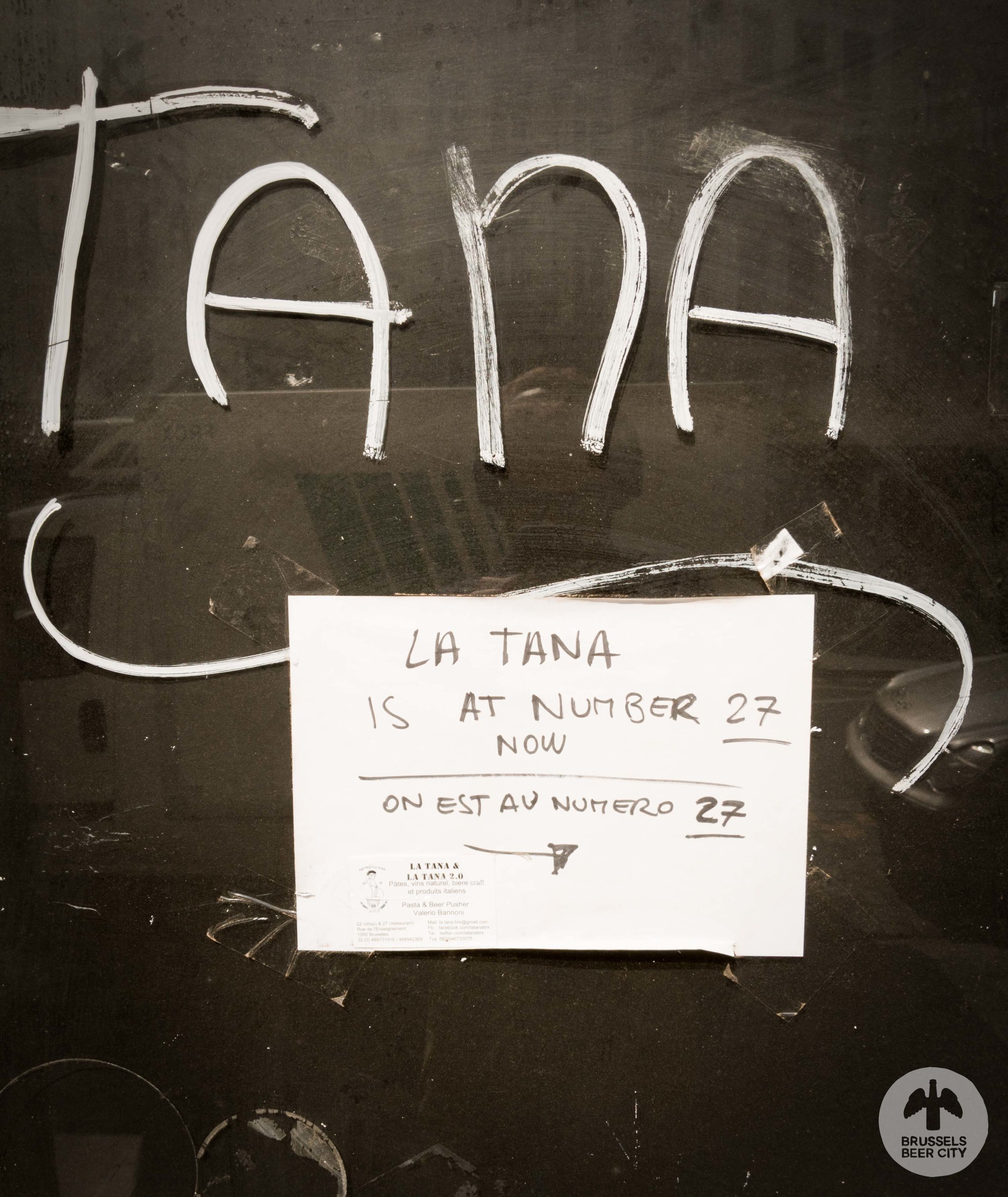

Compared to the controlled chaos of Friday night at Nüetnigenough, the following Monday lunchtime across town at La Tana is quiet. The restaurant has just jumped from number 10 across Rue de l'Enseignement to number 27 but the aesthetic is unchanged. On bare white walls are hung chalkboards with the day’s beer specials in yellow and green scrawl. There are nods to owner Valeriotto Bannoni’s hometown in black and white photos of the Colosseum on the wall.

An I Giallorossi football scarf hangs over the entrance to the kitchen, through which streams almost iridescent fumes of caramelising pork. Next to a couple of mobile tap installations crammed with brewery stickers are assorted beer kegs and a fridge stocked with Belgian and Italian beer, alongside bulbous bottles of Italian soda. Bannoni, in black Oerbier t-shirt and burgundy trilby, he points new arrivals – some stragglers from the weekend’s BXLBeerfest, others Flemish-speaking workers from the nearby government buildings – to tables covered in disposable white paper cloths with a jocular familiarity.

“I changed everything”

Bannoni didn’t need a wake-up call, just a chance and it came not long after he’d arrived in Brussels. Having started working in Rome as a chef aged 17, once he turned 18 Bannoni decided that if he we going to drink alcohol, he might as well drink the best he could find. “That was 2001, and the best beer [in Italy] was Belgian beer – tripels, quadrupels. And that’s what I started drinking,” he says. That soon led him to English and American breweries, and through to locally-produced artisanal beers from Italy’s emerging brewing scene.

“In Nüetnigenough, it’s maybe 80% that the beer we sell in the choice of the bartender after talking to the customer,” says Desmet. “We push things, suggest things, and see how people react”

Still in Rome at this time, he had easy access to great beer while working at a restaurant called La Tana. Bannoni and his boss there wanted to open their own place in the city but by the time a suitable place was found, Bannoni had already left for Brussels. He was six months on the job with a Sardinian restaurant when the owner of that restaurant took him aside and told him he would have to look elsewhere. Here was his opportunity.

Unwilling to return to Rome, and tired of jumping from one insecure gig to another, Bannoni convinced his Sardinian boss to postpone the sale while Bannoni and his brother – who had followed from Rome – weighed their options. “ After five days, we opened our own restaurant,” he says. “I changed everything.” Out went Sardinian cuisine and in its place came a Brussels La Tana, with the blessing of its Roman forebear.

The Hideout

The name, which means den or hideout, was important for Bannoni because the images it conjures up for him were the same that he wanted the restaurant to do for his customers. “A warm place to go, with people, to have a good time. There is warmth, beer, and food. You’re there, and you don’t have to leave quickly. That’s La Tana,” he says.

In jettisoning his Sardinian menu, he also made the decision to scrap a wine list and focus entirely on beer. His experience was bumpier that Desmet’s at Nüetnigenough. “At the beginning it was a little bizarre,” Bannoni says. “Everyone said it was not going to be possible – you don’t have wine, only beer. That’s not an Italian restaurant!”

The first customer that walked through La Tana’s doors and sat at a small, rickety table was confused by the menu he’d received. “Where’s the wine?” he asked. Bannoni explained that, yes, this was an Italian restaurant, but no, he was afraid that they didn’t have any wine to serve him: “Just artisanal Italian beer,” he said. And the customer, a Belgian, shot him a look of surprise: “Ah, because you make beer in Italy?”

Pasta alla gricia and Cacio e Pepe

18 months of handholding more bewildered customers later and Bannoni had successfully established La Tana identity as a place for quality Roman cooking – think Pasta alla gricia and Cacio e Pepe – and new and unfamiliar Italian beer from the likes of Baladin, Bibibir and others. In those early days, Bannoni often found himself explaining the backgrounds of the breweries he was serving, his commitment to small and independent producers, and how in fact the Belgian beers his customers were used to drinking were not always what they seemed. “People who thought Duvel was artisanal…You need Belgian people to tell Belgians that their beer is changing. Not me!” he laughs.

This educational mission was extended when, four years into running La Tana, Bannoni found himself accidentally opening a sister bottleshop, La Tana 2.0. While on the lookout for a cellar for the restaurant, the owner of an empty shop a couple of doors away on the same street invited Bannoni to have a look at the shop’s basement. The cellar was perfect but even better was the retail space above it. It was big enough for a small shop, which he soon filled with shelves and fridges stacked full of bottles and cans of his favourite Italian and international breweries, alongside bottles of olive oil and tins of Italian tomatoes.

The bottleshop takes up more of his time now. He misses mixing it with diners in the restaurant, so when the shop is closed he nips back over the road to take change of lunch and dinner service. He’s even compromised on his vision a little, with a selection of natural wines joining beer on the drinks list. “But, one red, one white, one rose,” Bannoni says.

“There’s no balance”

Even though he’s made room for wine now, it still confuses Bannoni why it took so long for others to go the other way and incorporate beer beyond the usual suspects into their restaurants and food. “It’s bizarre that you don’t have too many,” in Brussels, he says. “Either you eat well, and the beer list is poor. Or, you have a beautiful beer list and the food is not great. There’s no balance!”

“You need Belgian people to tell Belgians that their beer is changing. Not me!”

Over at Nüetnigenough, Desmet puts this historical anomaly down to a stubborn perception on the part of the city’s chefs that wine is the more malleable drink. “It’s harder to pair a beer with food than wine,” he says. Brussels native Dirk Myny of Les Brigittines posits a different reason. “Beer is sometimes connected to football, to cafégangers, beer bellies, and drunkenness. But it’s not that at all!” says Myny, who believes it is incumbent on people like him and Desmet to prompt, and where necessary challenge, their customers to consider beer as the equal to wine.

That this challenge has in the past been more ably taken up by the likes of Desmet and Bannoni suggests that foreign interlopers who fall in love with the city’s beer traditions, but have not grown up with its culinary diktats, are less constricted in their approach to pairing beer and food in their restaurants. Whatever is behind the emergence of a new wave of beer-positive establishments – and Desmet name checks cheese bar La Fruitière, run by a mother and son team from the French Jura, and fermentation shop/lab/school/food truck Fermenthings (a partly Belgo-Quebecois affair) – he’s happy to have the company: “They are doing something different… full of passion…and always learning and looking for new things.”

Lucky Brussels

And as good food paired with great beer has become less a bug than a feature of the Brussels restaurant scene, Desmet and his colleagues have been folded into the city’s beer community. A case in point is the BXLBeerfest, for which those Friday night and Monday lunchtime diners came to Brussels.

Desmet says that a chance conversation with Jean Hummler of Moeder Lambic led eventually to the founding of the festival (together with Kevin Desmet – no relation – and Vincent Callut); it has a strong emphasis on food, with stands and tasting sessions from a cross-section of the city’s best restaurants, cheesemakers, juicers, smokehouses, and taco wrappers. And slinging bowls of fresh spaghetti bolognaise to weary drinkers on a post-festival comedown on Sunday evening was Bannoni and his crew at La Tana.

That such a culinary spread is possible shows how far Brussels has come in the ten years since the opening of Nüetnigenough. It should at least give Desmet pause the next time he worries about the state of restaurants in his next ten years.

“We are lucky in Brussels, finally,” he says.