A History of Brussels Beer in 50 Objects // #15 Bottletop, Marchand de Bières

Find out more about Brussels Beer City’s new weekly series, “A History Of Brussels Beer In 50 Objects” here.

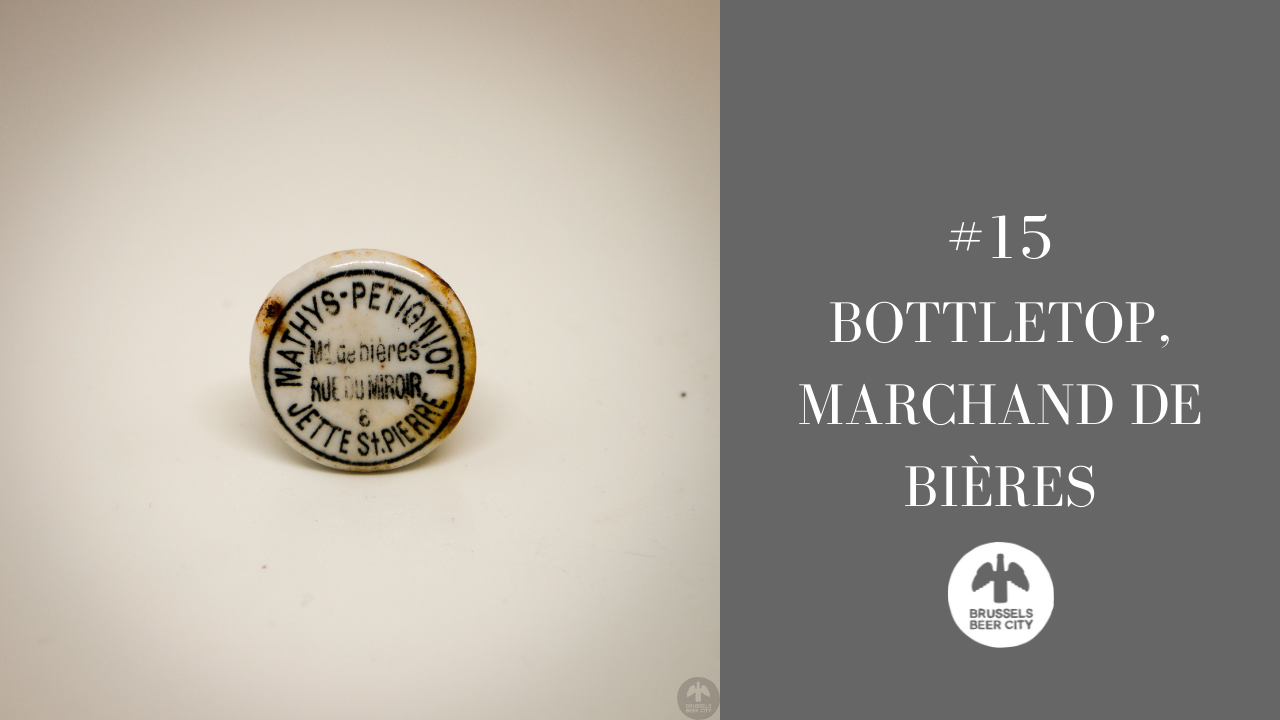

Object #15 - Bottletop, marchand de bières

19th century

Business Life

On May 3, 1867, a small notice appeared on the Journal de Bruxelles back page. Printed alongside advertisements for chocolate and hotels, it announced the sale of assets of a business on the Rue des Teinturiers:

1,000 barrels of excellent Lambic, Faro, and Mars beer, a portion of empty barrels and of hops, and the utensils of a marchand de bières.

The marchand de bières (“beer merchant”) was, Martine De Keukeleire says, one of four key actors in 19th century Brussels’ beer industry. Maltsters made malt, brewers turned this into beer, which cabaret owners served. But between brewery and cabaretier came the marchand de bières (also called the préperateur, or apprêteur).

The merchant’s job was to source Lambic and Mars beer from breweries, blend and condition it at their own warehouse for sale to cabarets and taverns. Sometimes merchants - “brewers without breweries'', commissioned breweries to make their beer. Others, described as “grands connaisseurs” - visited local breweries to source the best Lambics and Mars beers already in barrel.

However they sourced their base beers, the merchants then sweetened it, coloured it, clarified it, and packaged it as Faro, petit Faro, and table beer. To differentiate themselves from brewers, merchants might etch their names onto bottles or stamp it on bottle tops, like this example from Mathys-Petigniot, a marchand de bières from Jette.

Beer merchants weren’t always distinguishable from breweries. In 1822, Brussels did not make a distinction between the two, listing no marchand de bières in their annual business almanach. Breweries may have functioned as both, running, as historian Lucas Catherine describes, voortappen - where you could sit and drink - and tappen, shops that sold beer at various measurements, starting at the half litre. But by 1834 the number of standalone beer merchants had reached five.

By 1866 - a year before the liquidation of the business on Rue Des Teinturiers - Brussels’ business directory counted 100 Marchand en gros de bières indigènes et étrangères (“Wholesale merchants of local and foreign beer”). Such was the beer merchants’ success, and such was the need for space to store barrels of Lambic and other beers for up to three years of barrel-conditioning, that at one point in the 19th century beer warehouses made up 75% of the total warehouse space in central Brussels.

That list from 1866 is testament to the fact that the distinction between brewery and beer merchant remained ambiguous, featuring as it did a brewery like Wielemans Ceuppens - still located in the Marolles neighbourhood but on the verge of a move to a modern, purpose-built brewery in Vorst. And as the name of the category into which the city allotted them indicated, beer merchants had branched out from Lambic. From the 1850s onwards, Brussels’ drinkers had begun to get a taste for foreign beers, and beer merchants were keen to milk this growing market. By 1897, alongside the traditional listings for Lambic préperateurs and apprêteurs were mentions of Bass & Co. Pale Ale and Bavarian Löwenbrau, and large illustrations for Allsopp’s Stout Impériel.