A History of Brussels Beer in 50 Objects // #26 Plan for Brasserie Léopold, 1931

Find out more about Brussels Beer City’s new weekly series, “A History Of Brussels Beer In 50 Objects” here.

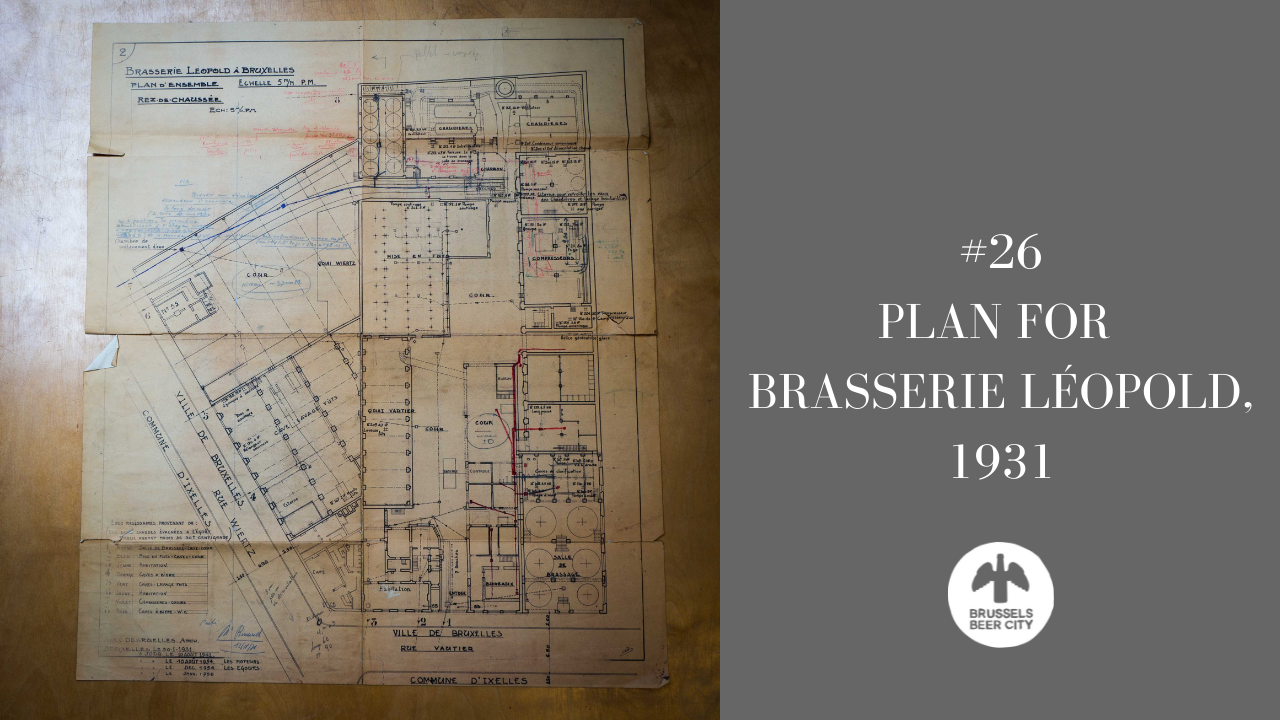

Object #26 - Plan for Brasserie Léopold, 1931

20th century

Brewery Life

Brussels in the 1920s was hit hard by a virulent case of Anglophilia, with cafés and estaminets overflowing with Stouts, Pale Ales, and Scotch. But the locally-brewed, Bavarian-inspired beers that had dominated brewing in Brussels before 1914 didn’t disappear altogether. Breweries continued to make Munichs and Bocks alongside their English equivalents, and advertisements like those of the Grandes Brasseries d’Ixelles - touting an eclectic range featuring an Export Helles, King’s Stout, Super Munich, and Gold Pearl Scotch - were commonplace.

It was a financially lucrative formula, ushering in an interbellum golden age for Brussels brewing which in turn launched an unprecedented building boom in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Wielemans-Ceuppens in Vorst commissioned a blocky modernist brewery from renowned architect Adrien Blomme, reputedly Europe’s largest in Europe when completed. Brasserie St Michel (later Vandenheuvel) expanded their footprint next to the Brussels West station in Molenbeek. And Anderlecht’s Grandes Brasseries Atlas erected a 30m-tall Moderne-style brewery tower.

Brasserie Léopold wasn’t as large as some of their rivals; in 1922, for example, the brewery consumed 1.6 million kilos of grain compared to Wielemans’ six million. But the Damiens family who ran Léopold were ambitious. Founded in 1860 - on a plot now occupied by the European Parliament - and sharing its name both with the next-door train station and the neighbourhood in which it was located, Léopold originally focused on producing Lambic and Faro. By the 1920s they too had started brewing foreign beer styles as the brewery’s director Georges Damiens was determined to not be left behind by his rivals elsewhere in Brussels.

If Léopold were to properly compete, though, Damiens decided they would need to expand. The existing brewery complex was adapted based on plans by local architect Alex Desruelles. It featured a home for Damiens, an on-site café, cellars for the brewery’s 22-tonne square open fermentation vessels capable of holding 223 hectolitres of beer, and three floors built for its 38-tonne, 325-hectolitre lagering tanks. A new brewery required new equipment - brewing vessels, piping, engines - to make the beers Damiens wanted. For this, local expertise was insufficient. Instead, Léopold’s director looked east, to the Stuttgart suburb of Feuerbach.

Feuerbach was home to the A. Ziemann Maschinenfabrik für Brauereienlagen. Ziemann were a well-established engineering firm that had built one of the first industrial breweries in China (Tsingtao brewery), as well as supplying Berlin brewery Berliner-Kindl with their equipment and - closer to home - had worked with Wielemans-Ceuppens before the war.

In June 1930 Ziemann drafted plans for a new six-kettle, steam-powered Sudhaus (“brewery”) for Brasserie Léopold capable of brewing 92 Zentner (4600 kg) of malt per batch. It included Laüterbottichen (lauter tuns), Maischbottichpfannen (mash boilers), and a Hopfenmontejus (a hop-back), which Ziemann’s engineers recommended to avoid the leaching of “unfavourable bitter resins'' from hop cones into Léopold’s beer.

Construction and delivery would take Ziemann eight months and installation on-site in Brussels a further six. And the damage this would cause to Damiens’ and Léopold’s finances? The princely sum of 18,168 Reichsmarks (€63,360).