Diaspora Season: Chapter 3 // Ciao, Belga!

Listen on Spotify and Apple Podcasts

The Brussels Beer City Podcast: Diaspora Season is about Brussels’ immigrant communities and the places they love to drink. From ice cold Sagres with piglet sandwiches and pintjes in old bruine kroegen, to creamy pints, fried plantains, and more, the podcast will explore the drinking - and eating - cultures of just a small slice of Brussels’ diaspora communities, in the company of people who have come from all over the world to make their home here.

Read more about the project here.

“I came here to Brussels to find work. Back in Italy, I had a job but no money, no contract. I knew Brussels, and Belgium, well. I thought, ‘I might as well try and find work there.’ So I sent around some CVs and when… I got lots of calls while in Rome offering work, I packed my bags. I thought, six months, let’s go. And I left [for Brussels].”

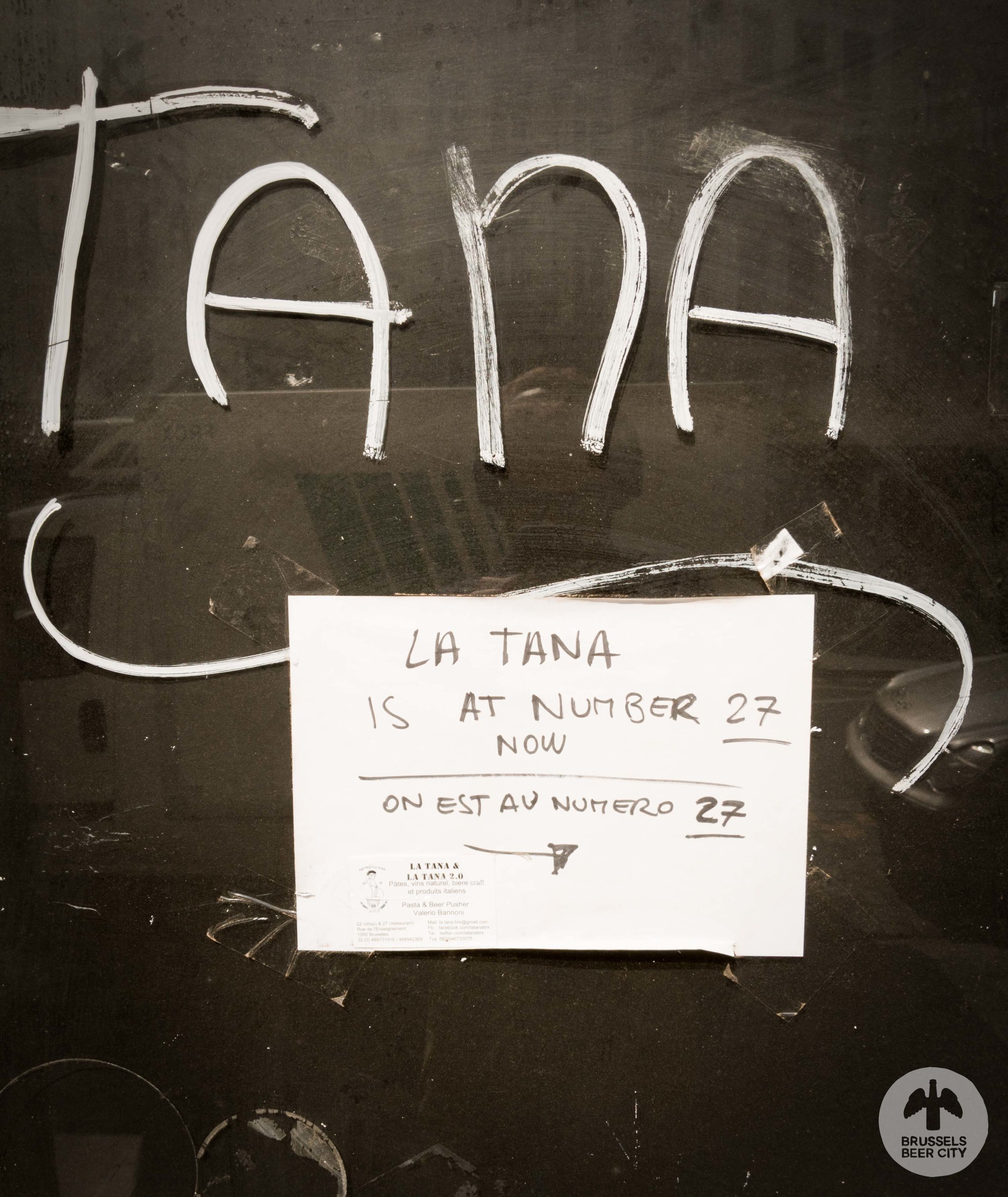

Those words are Valerio Bannoni’s. I spoke to him back in 2019 for a Brussels Beer City article on beer-centric restaurants. A chef by training, Bannoni was joined in Brussels by his brother and together they took over the Sardinian restaurant on Rue de l'Enseignement at which Bannoni had been working. Within six months they’d given it a new name - La Tana - and a new, Roman identity.

That meant no kitsch Italian frescoes or wicker basket Chianti bottles or Sardinian regional specialities. Instead, Bannoni developed a menu focused on Roman classics, paired with beer from artisanal Italian breweries. Brussels’ restaurants were not known then - or now - for adventurous beer lists. Either the food was good and the beer bad, or vice versa. It was a decision that wrongfooted some of his earliest customers. “Clients would say, ‘You don’t have wine, only beer. That’s not an Italian restaurant!’,” Bannoni said.

But beer was important in Valerio’s culinary education, and the Belgian and Italian brewing communities shared a longstanding mutual appreciation for one another - Belgian beer having been influential in Italy’s emerging beer scene, and Italian drinkers having been vital in supporting Brussels’ ailing Lambic brewing tradition when it looking like it might disappear.

It was logical for him to make beer essential to the La Tana experience. And it worked: “After a year and a half, everyone was coming to taste the best Italian beer.”

Since 2019 La Tana has moved to a new location and added some - natural - Italian wines to the menu, but the Roman identity and beer-stocked fridges remain, and diners kept coming. Why wouldn’t they? Italians have been feeding and slaking the thirst of Brussels’ residents almost since the first ones arrived in the 19th century. In the intervening years, through political upheaval, racism, discrimination, and tragedy, two things have remained constant: new Italian arrivals to Brussels have successfully mined the culinary and gustatory reputation of their homeland to make a life for themselves beyond the Alps; and the appetite of Brussels’ residents for the 'italianità they have discovered in these épiceries, delis, cafés and restaurants remained unsatiated.

The standard template for the Italian restaurant in Brussels has morphed over time as new generations of Italians arrive to adapt the formula to their own ends. Sometimes they have flattened their identities to appeal to a broader audience, at other times they have played to their regional strengths and focused on their own community, and some - like Bannoni at La Tana - have taken it in new or unexpected creative directions. Back in 2019, Bannoni told me that La Tana means lair or den in Italian, and he chose it because he wanted - like so many of his predecessors - to import to Brussels some of the cosy, warm familiarity of his Mediterranean home.

***

Almost the first thing Anne Morelli does when we’ve taken our seats at Le Cirio is correct my pronunciation. Morelli is a historian whose work has focused on the histories of religion and migration. She’s chosen to meet at Le Cirio - said, she says, with a hard “c” like cheerios rather than a soft “c” like cereal - for a drink (a Schweppes tonic for her and a traditional half-and-half for me) because of its personal and wider significance. Directly across the street from Brussels’ old stock exchange building, Le Cirio is the sole survivor of the first generation of Brussels’ Italian cafés. It was, in fact, already open for a half-century by the time Morelli’s antifascist Italian grandparents arrived in the 1930s seeking political asylum.

In telling the orthodox story of Italian migration to Brussels, two dates recur: 23 June 1946, and 8 August 1956. In 1946 the Belgian and Italian governments agreed the “Protocol concerning the recruitment of Italian workers and their establishment in Belgium”, by which Belgium would secure Italian workers for its coal mines and Italy would enjoy favourable rates for said coal. In the years after the signing of the Accords du Charbon, as it became known, Belgium’s Italian population ballooned from around 30,000 to over 200,000. 10 years later, 262 miners - 136 of them Italians - died in the Bois du Cazier mining disaster in Marcinelle. It focused attention on the dreadful working and living conditions of miners and their families and precipitated the premature end of organised Italian migration to Belgium. But, as Morelli’s own family history and the existence of Le Cirio show, the presence of Italians in the Belgian capital long predates 1946.

As far back as the 1850s and 1860s, Italians - mostly from Lombardy and the north - were living and working in Brussels. Some were organ grinders and glassmakers, mosaicists and newspapermen. But most worked in hospitality, as ice cream sellers, running small Italian bars, or manning high-end grocers-cum-cafés like Le Cirio.

Opened in 1886, it was part of a global network of salles de degustation (“tasting rooms”) built by the Italian tinned tomato baron Francesco Cirio to promote his products. His Brussels outpost is the only one that survives today, and it is also the only remaining Italian café from an era when downtown Brussels was dotted with Italo-centric cafés and brasseries, places like the Café Cremonesi or Au vrai Romain (“The True Roman”). Some, like Le Cirio, hawked vermouth to Brussels’ commercial elite, while others sold ice cream and coffee to the city’s Italian colony.

It was into this small community that Morelli’s Neapolitan grandfather and grandmother from Abruzzo arrived almost by chance in the 1930s. “They were antifascists, and so they fled Italy,” she says. Having first been expelled from Switzerland and then France, they made it to Brussels just before the war. Brussels had long a reputation as a safe haven for continental radicals, and in the interwar years Belgium’s Italian population swelled to 30,000. Their trajectory, and that of Morelli’s family, parallels the history of Brussels’ Italian diaspora.

Her grandparents settled in the city’s Italian quarter in the St Josse neighbourhood, where rent was cheap, landlords didn’t discriminate against Italians, and there was a thriving - albeit politically segregated - café culture. “The Romans said you have to give people bread and circus. But for the Italians in Brussels, it was bread and politics,” Morelli says. “People would go to certain cafes [where] they knew they shared with people there the same political or religious ideals.” Cafés in Brussels had always given succour to radicals, of which there were many of the Italian variety. In the interwar years there were antifascist cafés and their fascist equivalents, and after WWII there were Catholic bars, and Communist ones. Catholic associations and Communist ones. Catholic football clubs and their Communist opponents. “Italians were - and remain - more politicised than Belgians…[and] no one was going to each other's cafe. Obviously,” Morelli says.

Morelli’s family eventually moved to a satellite colony in Molenbeek, where they were joined by Italians - mostly southerners and Sicilians. They came to Brussels to work in factories, breweries, and on the era’s major public works: The 1958 Universal Exposition, and later the construction of Brussels’ metro. But the family matriarchs returned regularly to St Josse for grocery shopping. “We had to go to the Italian district…because nobody [elsewhere] knew what an aubergine was,” Morelli says. “The Belgians had never eaten them, [or] lentils, chickpeas. So what if we wanted to buy those things, not to mention mozzarella, we had to go [there].”

Italian grocers weren’t the only attraction; right through to the 1970s the area around the Rue de la Rivière, Rue de la Prairie Saint-François, and the Rue de la Poche was still home to most of the city’s Italian cafés and restaurants. These were family-run places, like Chez Inès, opened in 1944, or Al Buco, a known antifascist hangout. By the 1980s, however, the area’s Italian character was diminishing. Morelli’s family and others like them were leaving St Josse, Molenbeek and Anderlecht for the greener, quieter streets of Brussels’ outer boroughs. “It was a question of upward mobility,” Morelli says, of their migration first to Laken and then to the Flemish suburbs. “Originally, they went to the poor neighbourhoods because that's the only place where people will let them rent, and where the rents were affordable. But when they did a little better, they went to another neighbourhood with more gardens, trees, and more space.”

And wherever Italians went in Brussels, Italian hospitality followed. Researcher Gaëlle Van Ingelgem estimates that between 1946 and 1975 the number of Italian-owned hospitality businesses in Brussels grew from 13 to 69, and by the end of the 1980s almost tripled again to over 150. But in spreading out to the suburbs, the Italian template underwent a metamorphosis. It wasn’t enough to target the Italian diaspora communities, these restaurant owners needed Belgian customers too. So they became less idiosyncratic, offering a more flattened Italian experience that bent towards the tastes of their northern diners - think traditional Belgian brasserie spaghetti Bolognaise topped with generous quantities of grated cheese, or carbonara made with cream.

By the 1980s, Belgium’s Italian population reached 300,000 and even in 2016 the country marked 70 years since the Accords du Charbon Italian remained the second most-common foreign nationality in Belgium after French. The most visible evidence of their impact was the ubiquity of Italian restaurants in every corner of Brussels, and Belgium. But that’s too clean a narrative for Morelli, because it elides the challenges she and her contemporaries faced and suggests their integration was a seamless process. “It’s wrong. There was racism, there was discrimination,” she says, having herself experienced firsthand slurs shouted at her (“Morelli Macaroni”). It annoys her that people held up figureheads like Queen Paola, Enzo Scifo, and Elio Di Rupo as evidence of successful integration. “[But] this is the tip of the iceberg. For the others, it didn't go as well as you might think…It's not a fairy tale, it's a social story.”

Save for one or two hold-outs, Brussels’ Italian enclave in St Josse is gone, squeezed out by property speculation, the encroachment of the area’s unofficial red light district, and the natural transfer from one immigrant community to the next. But Le Cirio remains largely unchanged since its conversion in the 1920s into the café-restaurant it is today. In 2018 it underwent a months-long restoration, though these days it wears its Italian heritage lightly. Absent recently restored adverts for Bellardi Vermouth and bottled Americano cocktails, and the name above the entrance, you might not make the Italian connection at all. The drinkers and diners at adjacent tables to Morelli and me are loud Spanish-speaking tourists, and it’s as likely as not that Morelli is the only Brussels Italian in the building.

And the “social story” she refers to, of Italian migration and integration, hasn’t stopped. The global financial crisis in 2008, and the subsequent Eurozone crisis that rumbled on throughout the early 2010s, propelled a new generation of Italians on a transalpine migration to Brussels. Many of them are coming with university degrees with ambitions to find work in or around the EU institutions. And up there in the European Quarter, in the streets around Schuman roundabout, they will have found a cluster of Italian places where they could indulge, like their predecessors, in a bit of “bread and politics”.

***

Piola Libri is not just a wine bar. It’s also a bookshop, an art gallery, an events space, and a bookshop. It is, Silvia Pastorelli says, “a cultural point [for Italians], maybe even more so than Brussels’ Italian Cultural Institute.” It’s the books as much as the booze that first lured Pastorelli to the corner of Rue Correggio in Brussels’ European quarter. “I like looking at, seeing the books from the window and then realising it's a bar, it's a bookshop, it's both,” she says while sitting in the children’s book section. Piola Libri also provides welcome respite for Pastorelli - who works in EU affairs - from the politicking and networking of the other Italian establishments in the neighbourhood. “It doesn't feel like a bar in the European neighbourhood,” she says. It is, as on the evening we meet for a drink, as popular with families and kids running about the place as it is with drinkers reading the latest issue of the Internazionale newspaper over a glass of wine. “It's a completely different vibe to the spots near the Berlaymont around the corner. And this is why I like it.”

Before opening Piola Libri its Bolognese co-founder Jacopo Panizza, like Pastorelli, worked for environmental organisations in Brussels. Unlike Pastorelli, he tired of that work, deciding instead to launch his bar-cum-bookshop with another Brussels-based Italian in 2007. It’s not changed much in the intervening years. There are walls stacked with wine bottles, and others with books. Brasserie de la Senne glassware dangles from the kitchen ceiling, and black and white photos and Piola Libri merchandise have been hung from the rafters in the rest of the bar. Unlike Le Cirio, animated Italian accents dominate the terrace, but they’re complemented by Dutch, German and American-inflected English.

Treviso-born Pastorelli’s line that it was books that drew her to Piola Libri is only a half truth. “I come from the land of Spritz, and to have a Spritz made in the right way…[is] very important,” she says. “Nowadays, Aperol Spritz is super fashionable. But years ago, when I first was here, Piola Libri was one of the very few places in Brussels where you could find a properly made Spritz.” That was back in 2014, when she arrived in Brussels as part of this new generation of Italian graduates who moved north in search of work. She only lasted a year. “I don't think I understood Brussels…and was unfortunately sticking too much to the Italian crowd,” she says. Her compatriots stuck together, would go to Italian places, talk Italian at parties, and complain that the weather wasn’t the same as at home. “For a lot of Italians, home is still Italy.”

But after a brief interregnum in Amsterdam Pastorelli returned with a new job, a new attitude, and a more balanced relationship with her italianité. “I came back as an immigrant rather than an expat,” she says. “And Brussels opened up [to me] in all kinds of different ways.” What Piola Libri offered Pastorelli this time around, beyond well-made Spritz, was a comforting, if rough, simulacrum of the Trevisan osterias of her youth, places where she’d pass old men drinking red wine on the way to school, and see them in the same spot on the way home. Places which were good for a quick sandwich, a Saturday night dinner with friends, a lunchtime coffee for an afterwork glass of wine. “Affordable and unpretentious” places, she says. “And the atmosphere here [at Piola Libri] is very unpretentious.”

And if Piola Libri isn’t providing the requisite peninsular warmth or authentic atmosphere Pastroelli’s looking for, she still has her favourite Italian supermarket to fall back on. “You walk through the door [there] and it just smells like an Italian supermarket,” she says of Stival, a shop in Uccle that’s been importing food and wine to Brussels since 1949.

And despite her current semi-detached relationship with Brussels’ Italian colony, she’s also noticed the recent trend of new Italian ventures - exemplified by the likes of La Tana - that are eschewing the broad Italian identity popularised in the city in the ‘80s and ‘90s in favour of an increased focus on regionality. “Italy is [still] a relatively recent invention,” she says. “And the regions have a very strong cultural identity, from their food to the languages and dialects spoken there.” Now, there are more regionally-specialised bars, restaurants and épiceries - representing Friuli, Puglia, and even Molise (the Italian region that doesn’t exist). Their popularity among Brussels’ latest generation of Italian arrivals is not hard to understand, Pastorelli says: “They all just want their own different [products]. ‘I want my typical cheese’. ‘I want my special wine’.”

Maybe this is just history repeating itself. When it opened in the 1880s Le Cirio was selling Vermouth because its owners - and much of Brussels’ small Italian community - came from vermouth country in northern Italy. It’s no surprise that Brussels’ first pizzeria appeared in 1960 in the wake of Neapolitan and other southern Italians who’d arrived after WWII. Italians are, as Pastorelli says and her exacting standards of what makes a good Spritz attest, proud of their home regions. And Brussels already has enough “Italian” places, and if you’re going to carve out a niche for yourself in a crowded market, you might just have to mine the culinary bedrock of your little corner of Il Bel Paese.

***

It was during one of Brussels’ interminable Covid-19 lockdowns when the idea for MangiaSempre came to Giulia Bevilacqua. Originally from Perugia in Umbria (“Forza Grifo''), Bevilacqua was a translator by training but ended up in Brussels after an encounter with a Brasserie Cantillon beer while working in a bar back home. “I didn't like beer at all,” she says, but her interest was piqued when a bottle of Cantillon Kriek received a rapturous reception from her colleagues. “I fell in love [with it]. And so I came here to Brussels to work in beer.” First at Moeder Lambic on Place Fontainas and then at Cantillon as a museum guide, but when Covid hit Bevilacqua found herself locked indoors with little to do.

“When you're all alone and your family's in another country, and where the culture isn’t the same, it's difficult,” she says. So she started cooking - comfort food mostly, talking with her grandmother back home over Skype about what she was cooking and whether it could be replicated in Brussels, and trying to keep her connection with Italy alive through food. “Because Italy is [after all],” Bevilacqua says, “the art of the table.”

Out of this came MangiaSempre. It doesn’t at first glance look like it has anything in common with a place like Le Cirio, with its stripped-back minimalist interior - bare walls, wooden shelves filled with oddly-shaped pasta, dinky jars of red pesto, multicoloured cans of Brasserie de la Mule Lager and green bottles of Cantillon Gueuze - compared to the latter’s exuberant belle époque decor. But the spirit is the same. MangiaSempre - located on a quiet street between the Wiels art centre and Brussels’ football club Union St Gilloise’s home stadium - is part-grocery store, part-bar, part-deli, and full time culinary embassy for Bevilacqua’s hometown.

“I want to explain to people that Italy is not just a cliché. It's not all about Puglia or Sicily or Sardinia,” she says. “There are other regions. And I want to bring mine also.” Alongside the pasta, cheese, and wine, there’s also freshly-baked focaccia and takeaway dishes made on-site by Bevilacqua. The inspiration for a lot of these - pasta al forno, risotto alla norma - still comes from her grandmother back in Perugia. “She taught me how to cook, but via the Internet,” she says. “It's wonderful.”

Bevilacqua isn’t translating texts anymore - she got tired, she says, of people asking her to work for free. But that doesn’t mean she’s not still a translator, just of another kind. “The first thing I learned is that translation is an explanation from one culture to another. And that's MangiaSempre,” she says. “ I make my Italian recipes because I want to translate things from here into my culture, because I miss my culture.” The result is as much a synthesis as it is a translation, a fusion of where she came from with the place that’s given her a career perspective - and a partner - that she thinks wouldn’t have been possible back in Italy. “I tell people it's ‘Italian Zwanze’,” she says. “You come here [and] you come to Italy, but you're in Brussels. So I'll use my Brussels accent and…I want to celebrate this union.”

The vegetables she uses are Belgian, she sells burrata made in Brussels by Pugliese and Neapolitan immigrants with milk from the Belgian Ardennes, and the beer is all brewed locally. There are some lines she won’t cross, however, and unlike her predecessors Bevilacqua prefers to educate her Belgian customers rather than bending to their expectations. Even those close to home. “I am myself with a Brussels guy [and] sometimes he wants spaghetti Bolognaise. Or to make carbonara with cream. And I get mad about it,” she says. “People come here, they want pancetta in their carbonara and I just explain. No, man, you have to make it with guanciale [and] I can explain to you how to do it.”

Bevilacqua’s MangiaSempre isn’t a salle de degustation in the mould of Le Cirio or a straight-up supermarket like Stival, nor is it an ersatz osteria like Piola Libri or a more traditional restaurant like La Tana. She calls it a knabbelerīa, a portmanteau of the Flemish verb knabbelen - "to nibble" - and the Italian word stuzzicheria, or "place to nibble". A new form, maybe, and a new name, but the same mission as those first Italian entrepreneurs 150 years ago who tried to seduce their northern neighbours with Italy’s culinary charms.

“I think here people are sometimes a little bit cold,” she says. “I just want to give them a little bit of our warmth, a little Italian chaleur.”

Listen to the podcast now, and subscribe on the usual platforms.