The waiting is the hardest part // Brussels pubs on lockdown, and in limbo

On the evening of March 12, interim Belgian Prime Minister Sophie Wilmès made the announcement everyone in Belgium expected would be coming. As of noon the following day, Friday, the country was on lockdown (even if Wilmès herself stressed she didn’t want to use that word) - schools closed, all businesses shuttered except for those deemed “essential”. Bars did not fall into this category. That Thursday night, Brusselaars flooded the streets, jammed into their favourite bars - or whichever were still open - for a final round of pintjes until who knows when.

A month later, the bars are still shut, lockdown has been extended to May 3, and there is no date in sight when any semblance of normality will return - if ever.

There’s nothing particularly exceptional about the centrality of the cafe to Belgian life; Jeff Alworth, on the latest episode of the Cabin Fever podcast, argued persuasively that pubs have been a civilisational constant, and Boak and Bailey on their blog have written recently about how every culture thinks their relationship to the pub is exceptional. On the streets of Brussels, it’s the bars and cafés that are the most visible representation of our new normal. Cars whizz by as fast - if not faster - than ever. Buses and trams still trundle up and over the city’s hills. But just at the time when terraces should be heaving - at the craft beer bars of St Gilles, the Congolese bars of Matonge, the utilitarian bars for the city’s Romanian and Bulgarian populations, the 19th century laneway estaminets, the tired but tenacious old locals with their regular if diminishing clientele - they are empty.

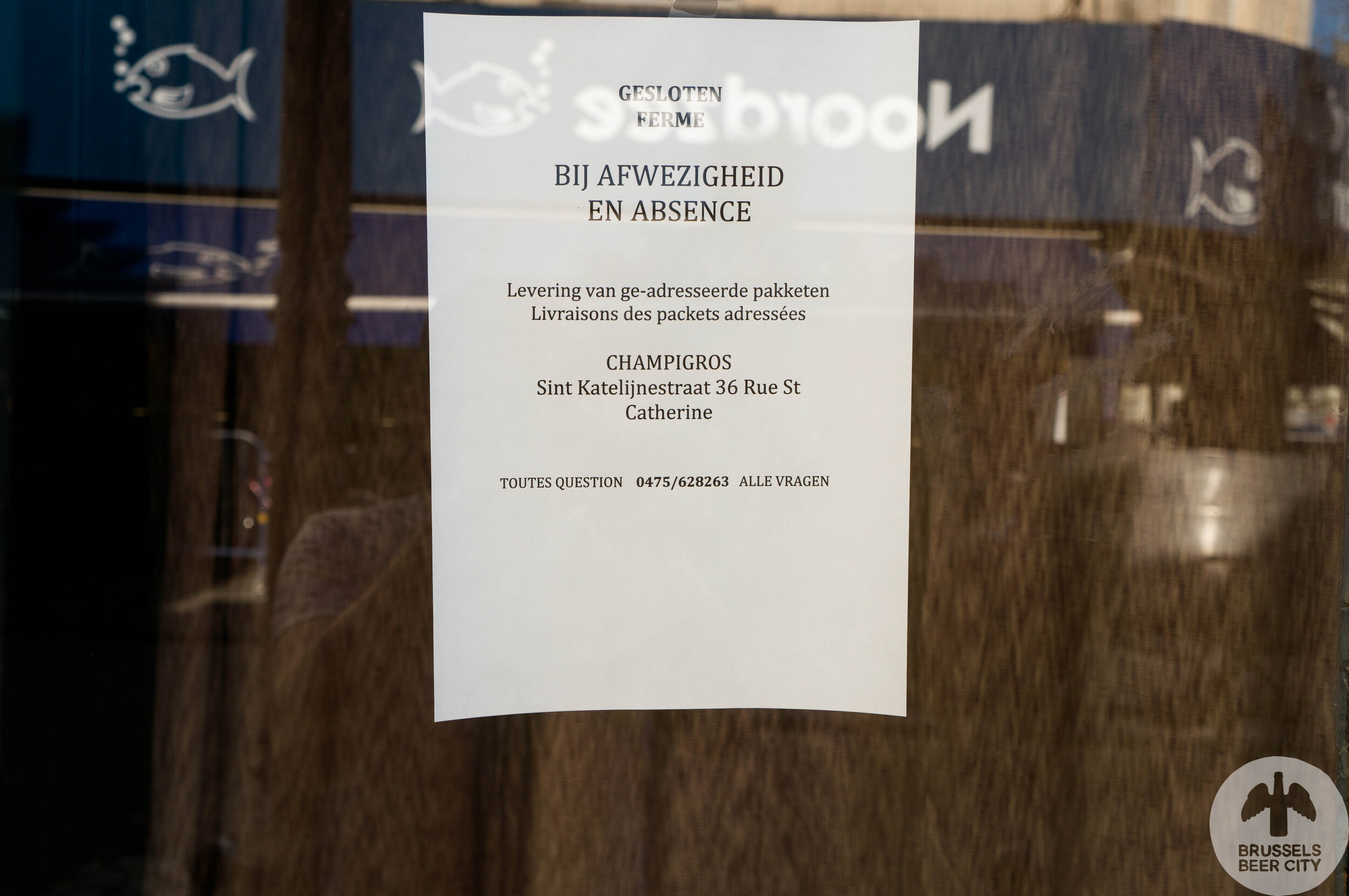

Stripped of their customers and their vitality, an unforgiving early April sun revealing every scuffed edge, grimy facade, and smudged windowpane, they seem permanently frozen in a pre-dawn stupor, as if just out of shout bleary-eyed revellers are slinking home.

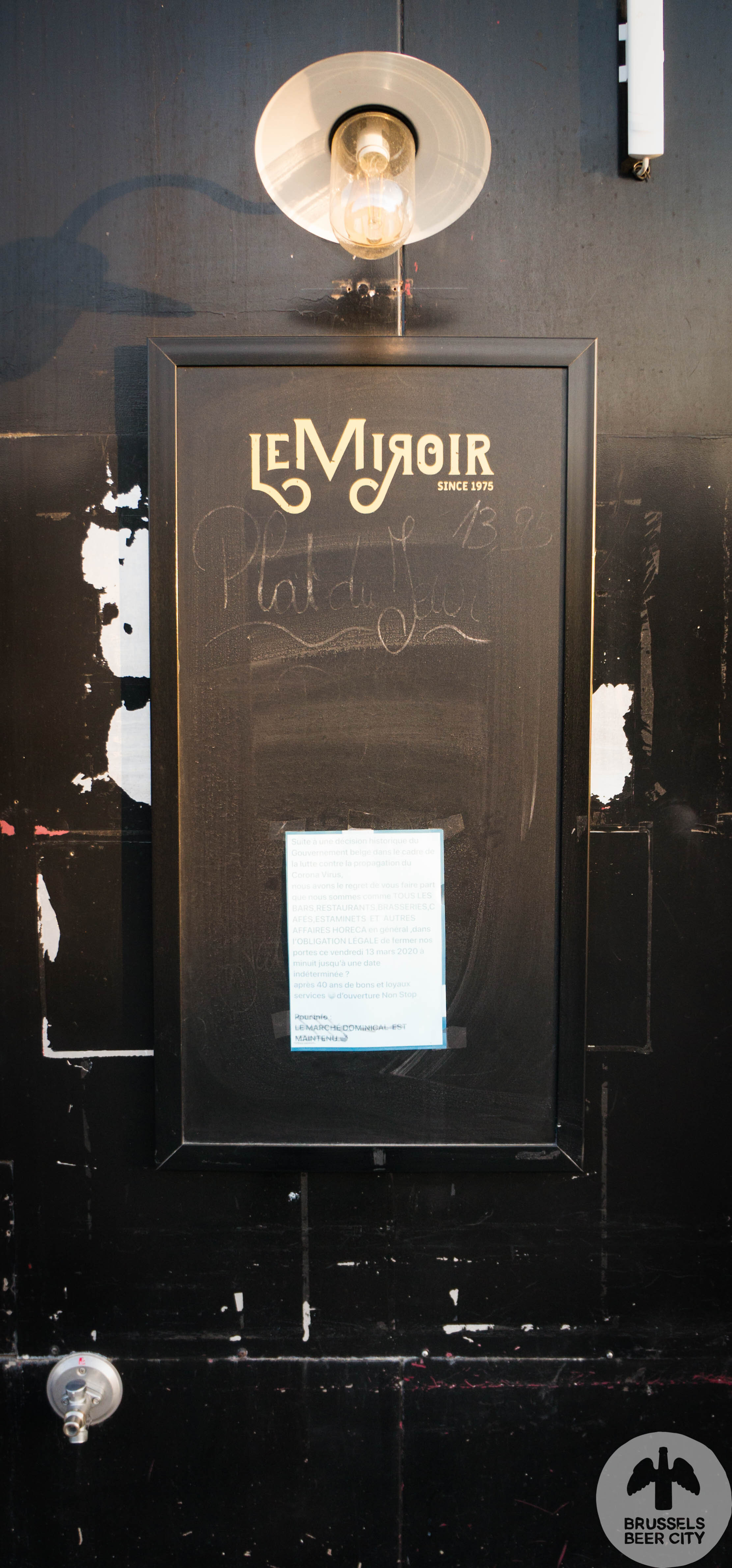

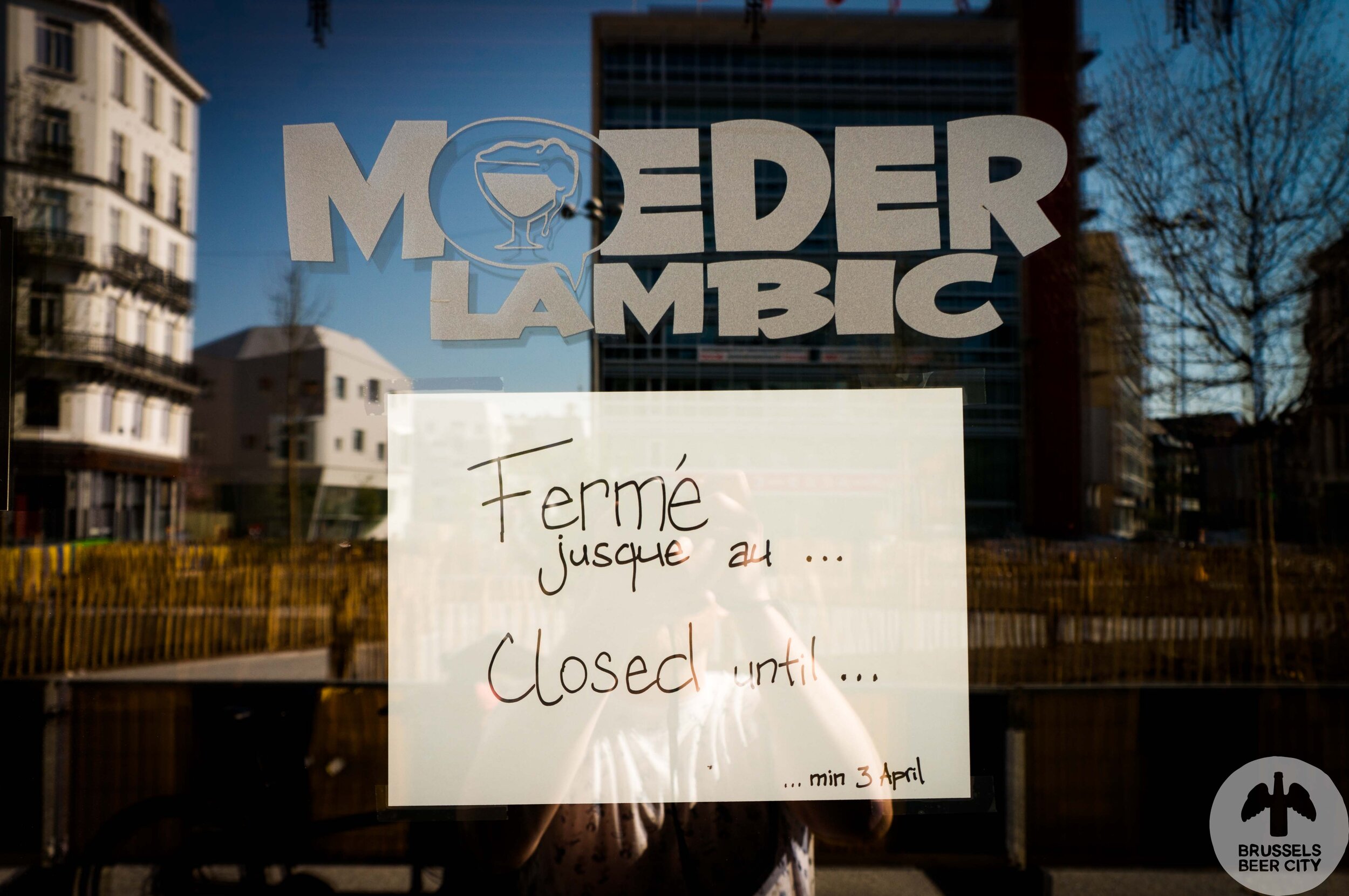

Some look as if the lights have just been turned off after a heavy shift, readying themselves for a new day. Others, with boarded windows and A4 explanations hurriedly stuck outside, belie this optimism. We do not know when they will open again, and some of them never will. But for now, they are in stasis, neither living nor dead. They just wait.

And the waiting is the hardest part.