Drinking in Koekelberg // The past, and a future?

“I was the future once”

Change comes slowly to Brussels. But it is coming to the corner of Brussels where the unfashionable communes of Koekelberg, Jette, and Ganshoren meet at Parc Elisabeth in a jigsaw puzzle of municipal borders. Hotel Restaurant Taverne Le Frederiksborg and Bar Eliza represent old and new Brussels, and and show in their contrasting fortunes how accelerating demographic changes are reshaping the neighbourhood. They also serve beer.

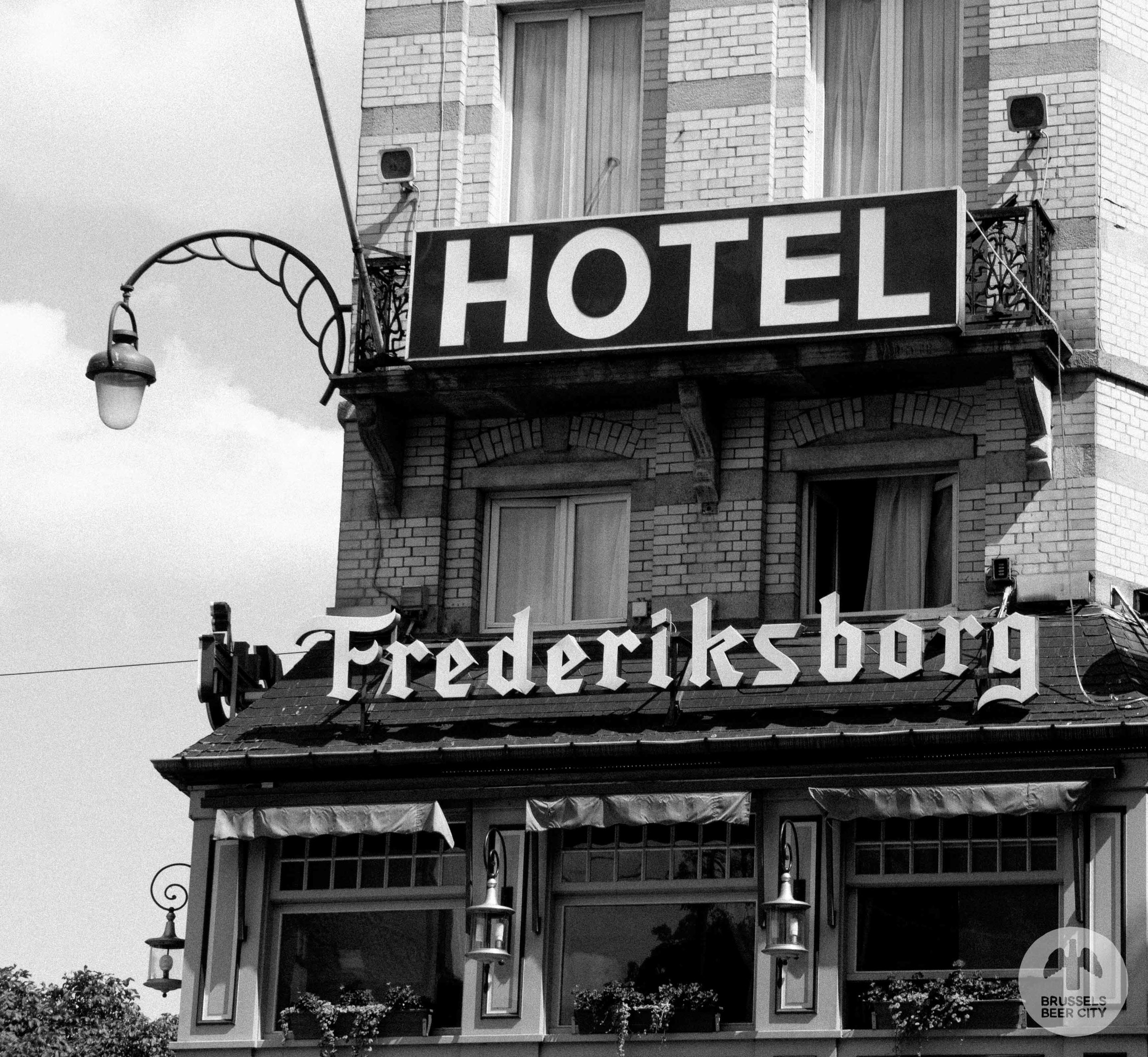

Frederiksborg - Danish Pre-modern

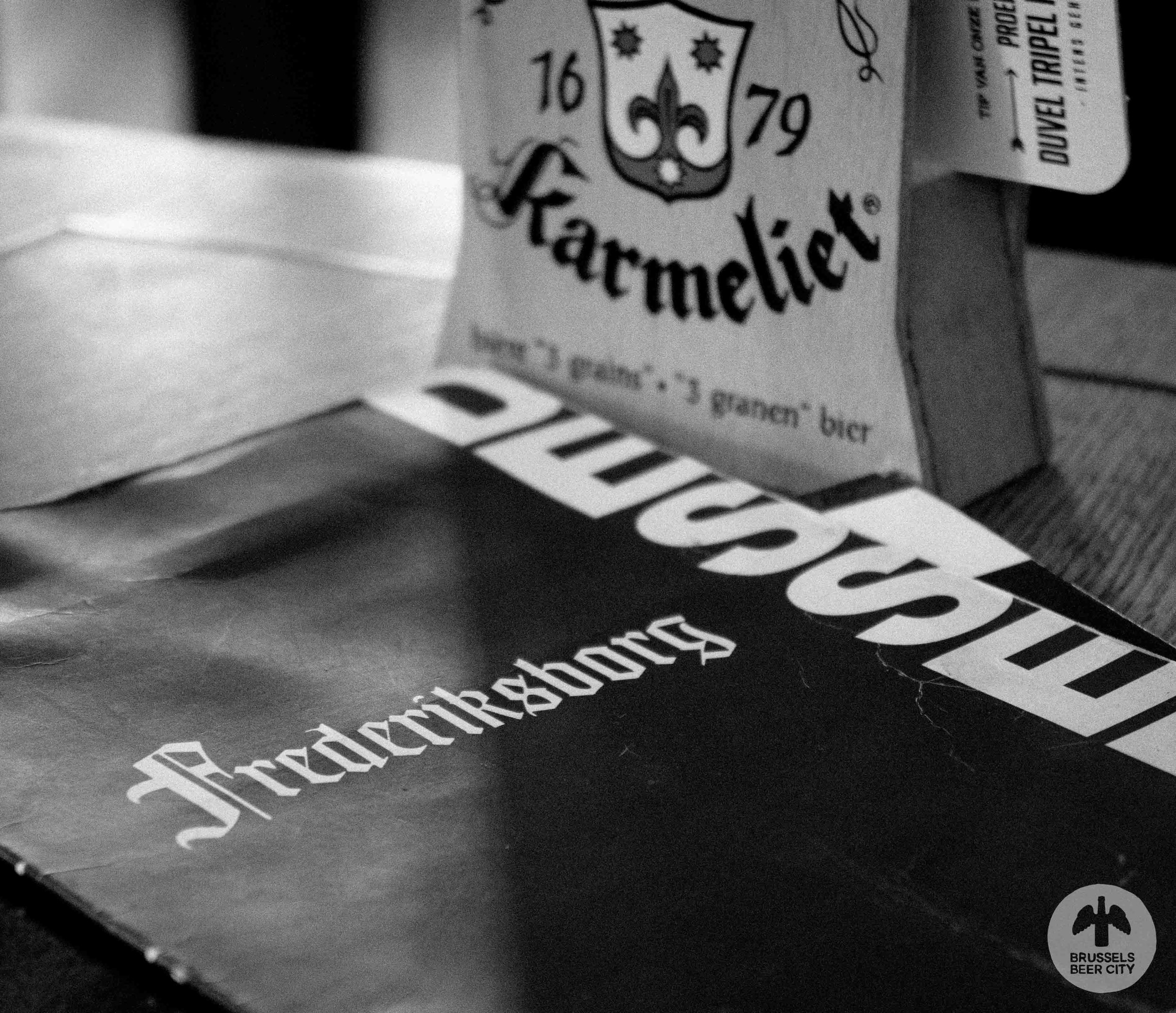

The smell of sweet, stolid Belgian cooking hits me as I pass through the wooden, brass-handled front doors. Carlsberg sits atop the beer list, betraying the bar’s connections to Denmark. It is to Carlsberg that Frederiksborg owes its existence.

Almost 40 years ago, Frederiksborg and two sister brasseries were opened as a marketing tool for the Belgian importer of Carlsberg, a man once known as the "Beer King of Brussels". It was a way to flog their import as a premium product in Brussels in a then-luxury Danish setting. Nothing unusual there - from the beginning of the 20th century, European beers have been popular in Brussels, and cafe owners aped the styles of Parisian cafes or British pubs. The other brasseries have since closed down or left behind their Danish origin. The threat of closure has loomed over Frederiksborg in recent years, but so far it has survived, a callback to an older Ganshoren.

And, judging by the Sunday lunchtime crowd, it is old Ganshoren (and Jette and Koekelberg) that is the bar's customer base. An elderly woman in the next booth over receives her Moules Frites from a waiter in black waistcoat. Later, she will politely complain to management that they were overcooked, but she eats them nonetheless. She is archetypal of early-Sunday Frederiksborg: retirees and pensioners, and soon-to-be retirees and pensioners. This is drab Brussels, a Brussels of post-war apartment complexes flanking wide, still boulevards, built for the car and the commuter. It lacks the youthful bar-and-food scene of Saint Gilles or the wealth of the salubrious southern communes. It's all a bit dull up here.

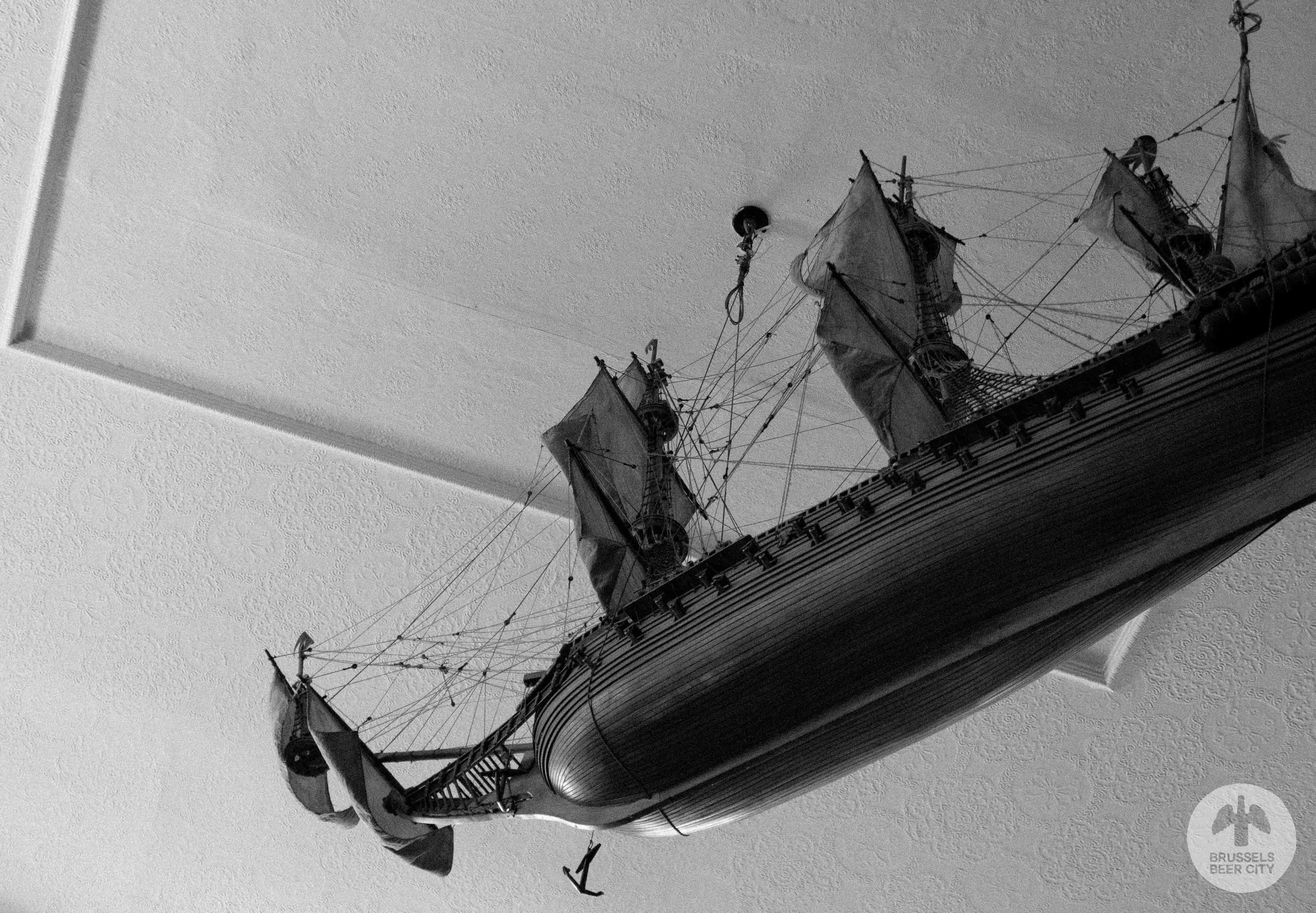

The bar itself is heavy, brown – dark-stained wood, leather banquettes, brown plastic air vents on the ceiling. The double height ceiling is dominated by a wooden model ship hung from the rafters. The bar has received a sort of a makeover since I was last in; the pea-green pastel on the exterior remains but salmon pink wallpaper has been replaced by a nondescript cream. This is not Danish design as we would know it now. Was it even then?

Ibiza chillout music plays incongruously in the background, eventually shifting to soft rock. Other than that, it's quiet. Out the window of my booth, the view across the street to the Koekelberg's monumental, Art Deco Basilique Nationale du Sacré-Cœur that dominates the skyline to the north of Brussels is obscured. The Basilica, like the bar, is a lumpen pastiche failing to replicate the original that hasn't aged well. Frederiksborg’s heyday, and that of its customers, is long past but the bar has for now received a stay of execution. New management took over in 2016, but the real estate is still owned by the family of Carlsberg importers that opened it with such fanfare in the 1970s. What they will do with it is anyone's guess.

Carlsberg - probably the best lager in Frederiksborg

It seemed churlish to try anything other than Carlsberg. It’s why the place exists. The choice was between a Flute or a Grand Danois. It being Sunday lunchtime, I went for the smaller serving. We drank a lot of Carlsberg in Ireland when I was younger. Beyond nostalgia I haven’t much affection for the beer. Here, it is perfectly serviceable, served at my table a yellow-straw and lingering foamy head. It does its job of being refreshing, with a surprising citrussy-hop aroma. Taking a sip, there is an initial malt sweetness and that comes through more as the glass warms up. There is some citrus hop flavour there as well, and a light bitter finish. This is a clean, uncomplicated and unremarkable pilsener. Light refreshing, it goes down well enough with a bowl of nut mix.

“I used to be with it, but then they changed what ‘it’ was, and now what I’m with isn’t it. And what’s ‘it’ seems weird and scary to me.”

Bar Eliza - The Prototype

Bar Eliza is the new face of this part of Brussels. 600m and light years away from Frederiksborg. Everything about this place - its origins, the customers, the look - screams now.

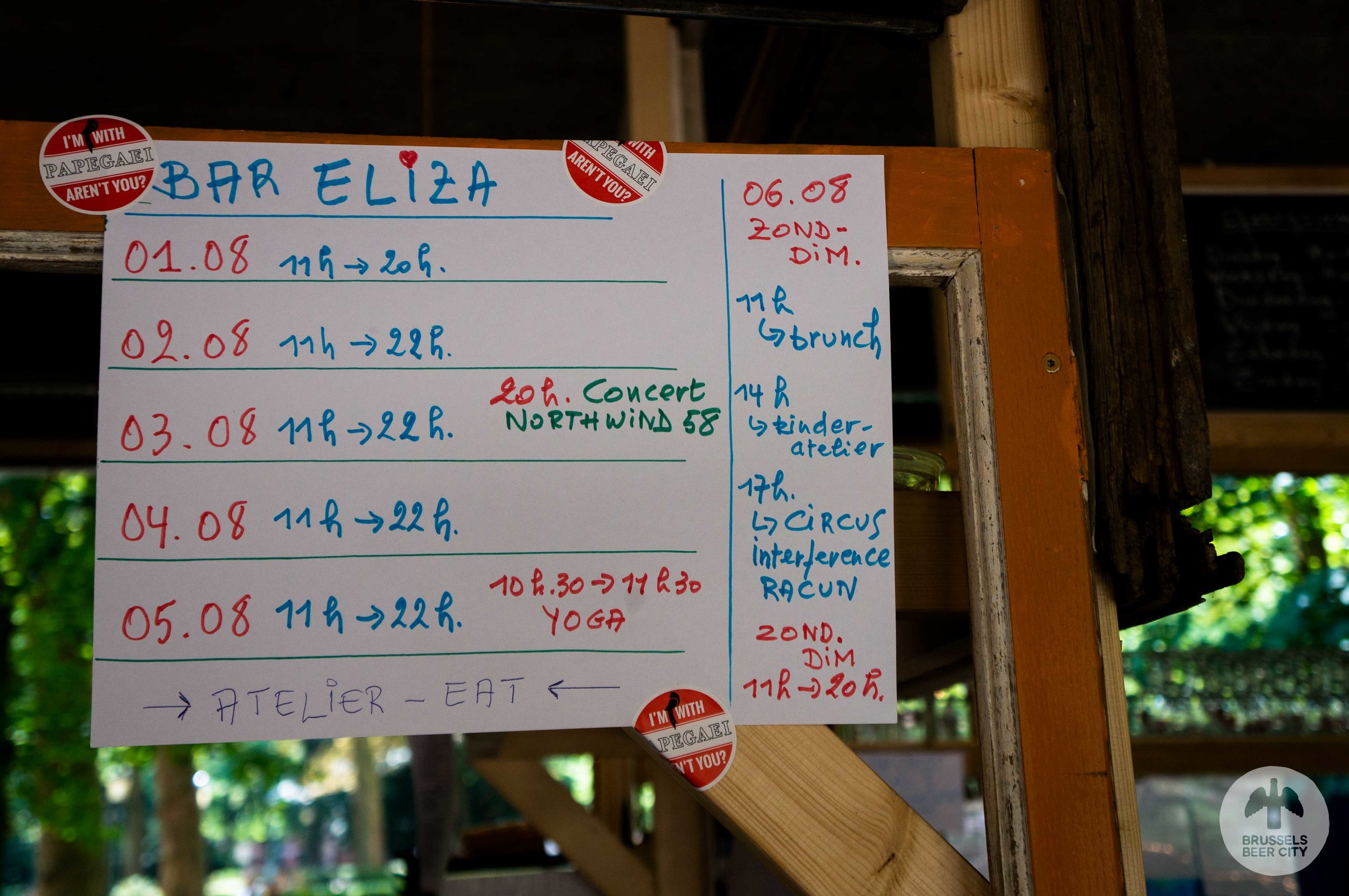

2017 is Bar Eliza’s second season. A former pavilion erected in Parc Elisabeth the 1950s to give local cards players a home that had fallen into disuse, it was taken in hand by several of the neighbouring Flemish community centres with a plan to transform it into a temporary summer bar. It was backed by a successful crowdfunding campaign - to which I indirectly (it was a birthday present) contributed - and was a runaway success in the summer of 2016, in a neighbourhood crying out for an informal, child-friendly bar.

It has returned for the 2017 summer season, just one of a new wave of pop-up park bars that are opening across Brussels’ parks. People are rediscovering the joys of outdoors drinking, none more so than the families who live around Parc Elisabeth.

If you could distill the left-leaning, alternative professional class of Brussels - usually those harbingers of gentrification, it wouldn’t look much different than the customers taking up the tables of Bar Eliza this Sunday morning. This is where the Camper-wearing, Brompton-cycling, organic-eating, Bionade-drinking Flemish middle class of Molenbeek, Jette, and Koekelberg come to relieve themselves of their children and relax with a beer or a coffee on the bar’s terrace. Children’s bikes and city bikes and cargo bikes rest up against tree tree trunks. Dutch is the dominant language on the terrace this morning, as it is most days. The odd word of English or French pop up now and then. You won’t find many jumpers draped on shoulders here.

Bar Eliza has what Frederiksborg doesn’t: life. Kids run around rough-hewn wooden castles, hollering and crying. Families sit around reading the Saturday papers, helmets hanging from repurposed folding chairs. The Flemish cool kids nurse their glasses of roses behind round sunglasses and angular fringes. The old neighbourhood is still there, a dog-walking older woman sitting down to sup on her Tripel Karmeliet as the nearby children gesture warily at her dog.

Where Frederiksborg is dour, Bar Eliza is open, light – bleached wood, minimalist by necessity and design. It is made from donations: recycled wood and wooden pallets, mid-century molded-plastic lampshades, and chipboard walls. The bar itself is made from repurposed window frames. Large holes have been smashed through the whitewashed concrete walls to make pane-less windows. Bar Eliza is not open in winter because it has no heating or insulation, isn’t hooked up to mains water or electricity, and doesn’t look very water-tight. Right now, the toilets have relocated to a nearby portakabin.

For people with young children, Bar Eliza has been a godsend. It is exactly what we need, at the right time. it’s perfect for me. But then, I’m not really representative of the wider population around here. That part of Koekelberg between the Charleroi canal and the rail line has a large North African population and a fast-growing Romanian community.

The latter is visible across from the park in a Romanian grocery shop and couple of bars on the Jetselaan. And, I’m told, by the groups of men that drink central European macro lager from plastic bags by the concrete entrance to the underground car park. Neither are much in evidence at Bar Eliza on the Sunday morning I am there. The organisers are making an effort to reach a more diverse audience, for example opening the bar up to Eid celebrations earlier in the year.

Zinnebir - the Brussels' People Ale

The beer that launched the brewing renaissance in Brussels. That’s probably hyperbolic, but Zinnebir is a landmark beer – the first beer from the first new brewery to open in Brussels in decades. It set the template for all the beers to come from Brasserie de la Senne – hoppy, bitter, and thoroughly drinkable.

Here, for €3 a glass, it’s a no-brainer. Deep yellow-orange and hazy, this Belgian Pale Ale has a beautifully fresh aroma, floral and citrus-fruity, with a very light hint of spice from the yeast. Drinking it in, at first there is light malt sweetness, followed by grapefruit, floral/herby notes, and a long, bitter finish. It’s medium-bodied and smooth, and the alcohol (6% ABV) gives it a little more heft and substance than the more critically acclaimed Taras Boulba. It is De La Senne, tot en met: a highly hopped blonde ale, bitter, refreshing, highly drinkable. It is increasingly a default beer for me if I see it on tap. One was enough though; it was still Sunday morning after all.

A local shop, for local people - but which locals?

Bar Eliza doesn’t have to be everything to everyone, and it probably can’t be. It’s an experiment that will run its course in September 2017. Its future is uncertain - there are plans to replace the building which houses the bar.

The demographic changes taking place in the neighbourhoods around Parc Elisabeth are making it more like urban Brussels - younger, more economically heterogeneous, and more ethnically diverse. These parts of Koekelberg, Ganshoren and Jette are losing their post-war, peri-urban feel. As this accelerates and new communities move in, looking for good value housing and greenery, new places will come with them and the established ones will adapt or wither.

Hopefully initiatives like Bar Eliza are less a beachhead for gentrification and more a template for future neighbourhood places by and for locals. For so long as there is demand, places like Frederiksborg will endure. Bar Eliza is ephemeral - maybe that’s part of the charm. For the moment, at least, it has given life to a hitherto staid neighbourhood, and given this dad somewhere to have a beer while his toddlers let off steam.